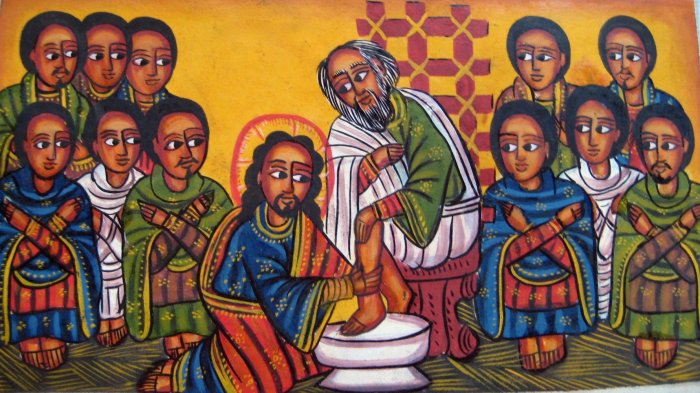

(The painting above, created by Koa Kohler, is entitled “Breaking Free”)

During my first two years in Butler, Pennsylvania, the church that I serve had a connection with 34 people who died as a result of drug overdose. When I say that there was a connection, I mean that those 34 people were either members of our church, or attenders, or related to somebody who is part of our church.

Two years. 34 overdose deaths touching our congregational family.

At the end of my second year in Butler, I stood in a funeral home, officiating at the funeral service for one of these 34 people. Just before the service, the cousin of the young woman who had died walked up to me with tears streaming down her face and spoke to me words that I will never forget. “My cousin was more like a sister to me,” she said, “and I just need you to know that there was more to her life than her addiction. She was a beautiful person who just got caught up in something bad that she couldn’t control.” Following the service for the young woman, her mother pulled me aside. “Pastor,” she said, “I don’t know what the churches of this town can do, but they have to do something. No more of this! Churches have to open their doors to addicts and their families every single day so that people can know that drugs don’t have to win.”

Here is the bottom line. During my first two years in Butler, God had to begin a massive reconstruction project on my heart and my thought processes related to addiction. I came to Butler harboring secret ideas—ideas about addiction only happening in the lives of certain kinds of people who simply need to get it together and make better choices. I now believe something very different. I now believe that the widespread reality of addiction in our community and in our world is the greatest spiritual crisis of our generation, one that demands nothing less than a transformed way of looking at the world.

And a transformed way of looking at the world is precisely what that part of the Bible we call “the Beatitudes” represents. We call them Beatitudes because that word, “beatitude,” is a derivative of a Latin word that means “blessing.” But what is seriously unnerving about the Beatitudes is who Jesus describes as being blessed in his kingdom. It is certainly not the people common sense would identify.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

(By the way, I am not sure that I have ever met anyone poorer in spirit than an addicted soul desperate for recovery.)

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.”

(By the way, I am not sure that I have ever encountered a deeper mourning than the mourning I have experienced in the lives of addicts and in the life of the family that surrounds the addict.)

There is a timeless relevance in the unsettling Word that Jesus offers to us through the Beatitudes. When we dare to apply the truth of the Beatitudes to our context, we find a word of radical hope even for addicted people and the families that surround them. In fact, when I quiet myself long enough to listen with my heart, here is how I am hearing the Beatitudes today:

“Blessed are those who are poor in the spirit of addiction. For theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn over addiction and the suffering it produces, for they shall be comforted.”

We always have to resist the temptation to make Scripture say something that it does not say. For example, when Jesus tells us that those who are poor in spirit and in a condition of mourning are “blessed,” he is not glorifying human suffering. He is not trying to get us to believe that it is a pleasant thing to suffer or to be devastated by addiction. But maybe Jesus’ point is that, in the world-altering grace of the Kingdom of God, addicted people can be spoken of as being uniquely blessed precisely because they know how desperate for deliverance they really are. The rest of us so often live in the illusion of being in control. Addicted people understand their need for salvation. The rest of us so often fall into the trap of distorted self-reliance, believing that we have no need for a savior. Addicted people are often more available to God than everyone else, precisely because they see (in a way that others cannot) that they are up against a struggle that demands a saving grace of supernatural proportions. That is why an addict can rightly be described as living in a condition of blessing—not because their addiction is good, but because their potential for recognizing the urgency and power of God’s deliverance is good.

If that is at all true, if you hear Jesus speaking a word of radical hope to the addict through the Beatitudes today, then I am inviting you to think differently with me about the reality of addiction. Here is how.

First, refuse to allow yourself to become cynical or coldhearted about the reality of addiction. Because here is the truth: Jesus never stops in his supernatural efforts to bring deliverance to addicted souls. Jesus never stops.

I heard a pastoral colleague recently (not from this community) lamenting hurtful words that she heard spoken in one of her church’s adult Sunday School classes. The hurtful words sounded something like this:

We need to stop giving these addicts Narcan because all they’re going to do is overdose again. It is a sinful waste of time and resources to keep people alive if they are just going to choose to die.

Can you imagine being the parent of an addict and hearing something like this from a Christ-following brother or sister? The pastor of that congregation put it this way:

“A statement like that indicates that our theology has not kept pace with our context. For me, this is a pro-life issue. I am a pro-life pastor who believes in a pro-life Jesus who never quits in the work of offering eternal life that he makes possible. And neither should we.”

Do not allow yourself to become cynical or coldhearted about the reality of addiction. Because Jesus never stops in his supernatural efforts to bring deliverance to addicted souls.

Second, refuse to allow yourself to become discouraged in the struggle against addiction. Be sad about it. Be heartbroken. Be devastated at times when the situation calls for it. But refuse to plant spiritual roots in the spoiled soil of discouragement. Why? Because Jesus Christ will not rest until every addict experiences the blessing of a complete deliverance from an enslavement to addiction. For some, this deliverance might take a portion of eternity that we do not yet see. But rest assured, no addict lives outside the boundaries of Jesus’ love and the redemptive grace that he is so very desperate to offer to addicted souls. And if that is true, if Jesus is on the side of the addicted and committed to their deliverance, then HOPE is our “go-to,” not discouragement. Therefore, refuse to allow yourself to become discouraged in this. Instead, commit yourself to participating in the saving work that Jesus is doing in the world by coming alongside the addicted in whatever way is appropriate. Become a part of that saving work.

Finally, refuse to allow yourself to become judgmental or dismissive about addiction, because, here is the thing: Every single person reading these words is caught up in the rhythms of addiction. You might not be addicted to a substance, but I can practically guarantee you that you are addicted to something. We all are.

We are addicted to hurtful ways of thinking that inspire us to kneel down at the altar of our own distorted opinions.

We are addicted to hatred that prevents us from loving, forgiving, and hoping.

We are addicted to patterns of behavior that are hurtful to ourselves and the people around us.

We are addicted to false stories that prevent us from embracing the truth about ourselves and our relationship with the world.

On Facebook, one never has to look far to find someone spouting a passionate opinion (or sharing a convenient meme) about a particular subject. Politics. Religion. Movies. Sports. Hollywood. Current events. When I stumble upon such conversations, it often sounds less like the gracious pursuit of truth. In fact, it often sounds more like a bunch of addicted people getting high on the drug of their own opinions and their forced certainty.

Here is my point: When we speak of addiction, we are not speaking about “those people.” We are speaking about all of us. Because an enslavement to some kind of an addiction is a reality for all of us. When we are in relationship with Jesus, he brings us into a lifelong recovery that manifests itself as a journey of living one day at a time without the particular distortions to which we have become addicted. In that regard, the recovering addict has much to teach the church about what it means to be authentically Christian.

So, I invite you to a refusal. Refuse to allow yourself to become judgmental or dismissive about addiction. Because every single person reading these words is caught up in the rhythms of it in one way or another, and, thanks be to God, Jesus is not giving up on any single one of us!

For the last year at Butler First United Methodist Church, we have held a Saturday evening worship experience that we call “The Bridge.” Everyone is invited to the Bridge, but we offer a particularly pointed invitation to those who struggle with the reality of addiction and their families.

Why do we call it “The Bridge”? Because a bridge is precisely what we believe Jesus to be. He is the bridge from isolation to community; from despair to hope; from addiction to recovery; from being lost to being found.

We never know who is going to show up at “The Bridge.” Nor do we know exactly what will happen in each week’s worship. To be completely confessional, we don’t really know what we are doing with this ministry. (Is it okay for a pastor to admit that?!) But, every single week at “The Bridge,” it feels like we wade into deep and important water.

Last Saturday night, a man stood up during prayer time at “The Bridge,” introduced himself as a recovering addict, and announced that, as of this week, he will be six months clean. He just wanted to thank Jesus Christ for his transformed life.

Following the service, this man came forward to pray with me. When I asked him how we should pray, this was his response: “Pray that more and more people in our community will come to understand what I have come to understand.”

I couldn’t help but ask the question. “And what is it have you come to understand, Thomas?”

“What I’ve come to understand,” he said, “is that addiction is never the end of the story that Jesus writes in our lives. It might be a chapter, or even a series of chapters. But it is never the end of the story.”

That is nothing less than the Gospel, offered by Jesus through the Beatitudes and spoken afresh by a recovering addict in downtown Butler. “Addiction is never the end of the story that Jesus writes in our lives.”

That Gospel is the foundation of the radical hope offered to us by Jesus Christ, in whose name we stand against addiction and in whose name I gratefully write.